1. Introduction

There are many issues to cover in the study of quotation. For example, how does one distinguish direct speech from indirect speech? What is the nature of the quoting verb (including verbs of thought or knowledge)? What can be quoted—including loanwords and ideophones—and how does this interact with phenomena such as argument structure and switch reference? How do quotative particles function within a clausal spine that involves higher-level propositional operators?

This paper describes quoted speech and related phenomena in the Maxakalí language, an SOV ergative language belonging to the Macro-Jê stock (Nikulin 2020; Rodrigues 1999) with approximately 2,000 speakers in Minas Gerais, Brazil (SIASI 2014). Initial descriptions of Maxakalí quoted speech can be found in Popovich (1985, 1986). We have collected data with speakers over the last decade, including spontaneous speech recordings, to verify data collected in elicitation and in less-monitored speech.

2. Quoted speech

According to Clark & Gerrig (1990), quotations are a special form of language use, through which the speaker can report in the present conversation what someone has said in a preceding conversation. The authors define three types of quotation: direct, indirect, and free indirect (with this third type of quotation indicated by # marks instead of quotation marks). To illustrate these three types of quotation, we reproduce some examples in (1–3) (Clark & Gerrig 1990: 786):

- (1)

- Direct quotation

- And I said ‘Do you mean for lunch or dinner?’

- (2)

- Indirect quotation

- And I asked her whether she meant for lunch or dinner.

- (3)

- Free indirect quotation

- And I said #Did she mean for lunch or dinner?#

The three quotation types differ in vantage point; that is, the speaker decides which ‘role’ he/she is demonstrating. The main difference between these three quotation choices involves the manner of the speaker’s perspective denotation. That is, in direct quotation (1), the speaker uses the pronoun ‘you’ with the referent being the source interlocutor and thus directly reproduces the source statement for the current interlocutor. In indirect quotation (2), the speaker reports a paraphrased version of what was said, changing pronouns as necessary to maintain referents in the present conversation. Finally, the third type of quotation, free indirect quotation (3), is also said from the speaker’s perspective but, differently from simple indirect quotation, partially reproduces the source dialogue with an interrogative embedded clause. As explained by Clark & Gerrig (1990: 787):

In the direct quotation, the vantage point is [the] original one, and it dictates the choice of you and the present tense of do. In the indirect quotation, the vantage point is [the speaker’s] current one, which leads to she and the past tense meant. In the free indirect quotation, the vantage point is also [the speaker’s] current one, as reflected in she and meant, but the embedded clause is interrogative (‘Did she …’) rather than an indirect question (‘whether she …’).

Indirect quotations are descriptions, while direct and free indirect quotations are demonstrations. Distinct from descriptions or indications, the function of a demonstration is to enable others to more clearly envision or imagine depicted events or previous conversations. Quotations are usually introduced by verbum dicendi verbs and constitute the direct object of such verbs. As will be presented later, direct quotations in Maxakali appear as the internal arguments of a null verb (in a similar way to what was proposed by Hale & Keyser 1993, 2002), alongside the presence of an external argument identified by the ergative postposition te. Quotations, under this analysis, are semantically incorporated as the internal argument of an active null verb, leading to the outward appearance of an unergative construction.

3. Background: The Maxakalí people, language, and previous work on quotation

The Maxakalí language is the only extant language from the family of the same name, which is itself a branch of the Macro-Jê stock (see Nikulin 2020; Rodrigues 1999). It is spoken by approximately 2000 people (SIASI 2014) in the northeastern region of the Minas Gerais state in Brazil. Their traditional lands covered the valleys of the Jequitinhonha and Mucuri rivers, but nowadays are restricted to five villages (Pananiy, Kõnãg Mai, ĩmmoknãg, Apne Yĩxux, and Apne Ixkot Hãmhipak) near tributaries of the Mucuri river. They still preserve their traditional religious practices, and the language continues to be passed on to newer generations, assuring language survival for at least the next generation.1,2

The most comprehensive work about Maxakalí syntax is the doctoral thesis of Campos (2009). He demonstrates in it that Maxakalí is an active ergative language due to a split between agentive and non-agentive intransitive verbs.3 A and SA arguments are identified by an ergative marker te, and are differentiated from SO arguments, which are unmarked. This is illustrated in the examples in (4).

- (4)

- a.

- Arguments (A)

- Kokex

- dog

- te

- ERG

- pãmãg

- trap

- putxok.

- disarm

- ‘The dog disarmed the trap (unintentionally).’

- b.

- Arguments (SA)

- kokex

- dog

- te

- ERG

- pũn.

- jump

- ‘The dog jumps.’

- c.

- Arguments (SO)

- kokex

- dog

- mõyõn

- sleep.REAL

- ‘The dog sleeps.’

Popovich (1985: 36) states that the default word order in Maxakalí is SOV, based on evidence from phonological phrasing. He argues that a phonological phrase spans from the beginning of the clause to the end of the predicate, with each postposed grammatical phrase corresponding to a separate phonological phrase. Therefore, while SOV and SV orders are uninterrupted by any pause, other constituent orders like SVO or VS are marked by a pause between the verb and the following constituent. Silva (2020) analyses Maxakalí as a language with split ergativity conditioned by mood: on the one hand, the realis mood has the ergative argument (A) marked with the postposition te with an unmarked absolutive argument (S, O).4 On the other hand, the irrealis mood, used in most imperative constructions, in purpose clauses, and in clauses beginning with the inference evidential pa ‘seem’, shows a split where some intransitive verbs (inactive verbs) must express the subject (SO) the same way as O, while others (active verbs) do not (SA). This distinction is provided lexically; i.e., there is no way to tell in which group an intransitive verb belongs, outside of these alignment patterns. As we will discuss below, syntactic alignment and word order are critical for understanding quotation in Maxakalí.

Regarding quotes in Maxakalí, Popovich (1985: 41) says that

[q]uotations are introduced by the preceding quote formula in a fixed way by an upglide and brief pause. This pattern may accompany [tæʔ] ‘subject marker’… or a conjunction…. The word that functions as ‘unquote’ [kačĩñ] ~ [kah] literally means ‘like this’. It is used optionally. It has its own intonation pattern and does not follow the normal rules which function at the end of paragraphs or clauses….

The immediate question is thus whether kaxĩy (transcribed as [kačĩñ] by Popovich) is a quotative verb because of its final position in quoting sentences, or is a discourse marker indicating the end of the quote, or perhaps just an afterthought. As we will see in the next sections, determining the syntactic category of kaxĩy is difficult, as it may also be used in other constructions. It is nevertheless possible to make preliminary assumptions about it, and about quoting strategies in general, in a way that opens new research paths for a deeper understanding of this phenomenon and Maxakalí syntax.

4. Direct and indirect quoting

Maxakalí has been described as having both direct and indirect quotation (Popovich 1986: 355). For direct quoting Popovich presents the schematic formulas reproduced in (5):

- (5)

- a.

- Speaker

- te

- quote

- b.

- Speaker

- te

- verb of speech

- hu

- quote

The marker te is argued in that work to be a “transitive subject indicator” (an ergative postposition in our analysis) and hu a “logical sequence” conjunction (a cause and consequence conjunction in our analysis). He posits that there is no verb of speech in the formula in (5a), which encompasses over 90% of the tokens of direct quoting. However, in his work from 1985, Popovich says that kaxĩy ‘to be this way’ can appear optionally after the quote. In this case, the intonation pattern, as mentioned in the last section, is different from that of a quote without kaxĩy. This structure indeed appears quite frequently in our data, so the structure in (5a) would be better represented as in (6):

- (6)

- Speaker te quote (kaxĩy)

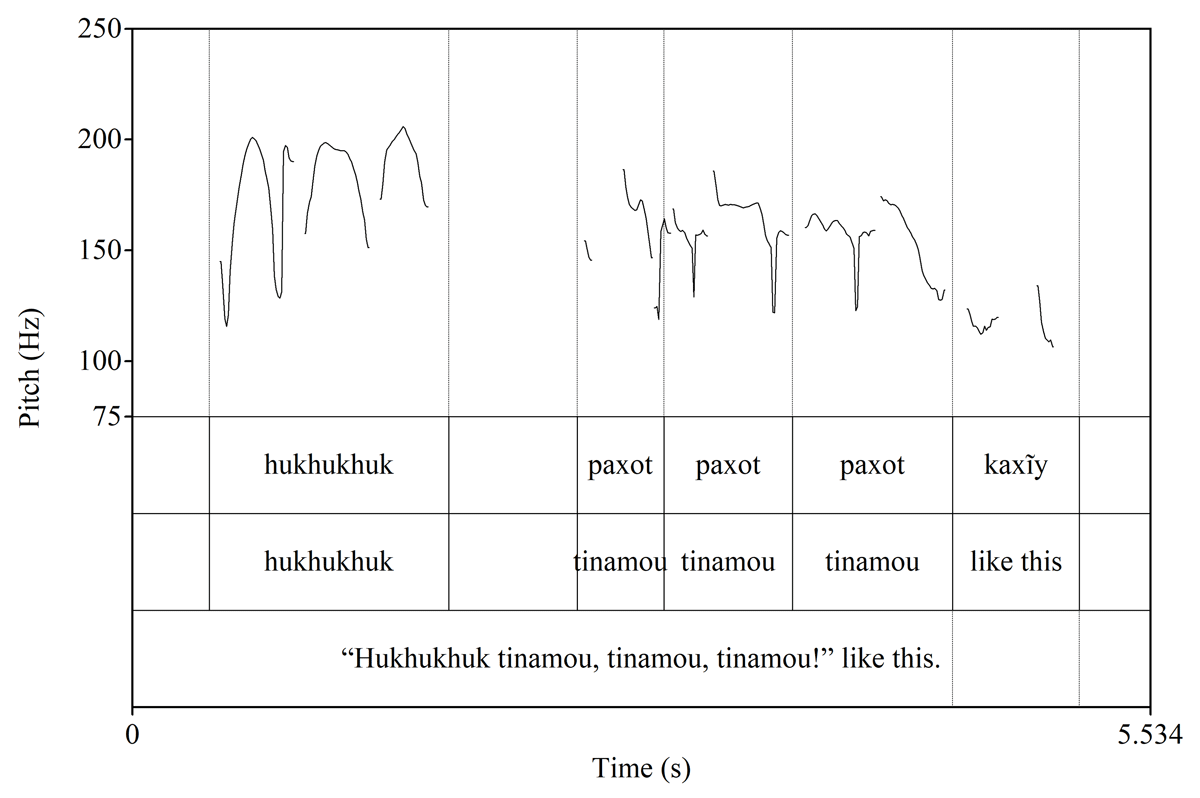

The formula above differs from that in (5a) in that it includes kaxĩy as an optional element at the end of the sentence. When present, the pitch on kaxĩy is rather low compared to the rest of the sentence: when asked if the pitch in kaxĩy could be maintained with the same height, speakers tended to find it strange. Figure 1 below shows a prototypical example of this kind of pitch drop. It is a quote involving the lyrics of a ritual song in which the tinamou bird (Tinamus sp., Portuguese macuco) is called.

We have found numerous examples with the structure in (6). Some of them are provided below:

- (7)

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- kakxop

- child

- ũ-nãhã-Ø.

- 3-fall-REAL

- The woman said: “The child fell”.

- (8)

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- ũg=nãhã-Ø

- 1.SG=fall-REAL

- kaxĩy.5

- this.way

- The woman said: “I fell”.

The most observable indication that the quotes in (7–8) constitute clauses distinct from the matrix sentence lies in the fact that the 1.SG clitic does not attach to the te postposition that precedes it, as it would in a simple clause. Compare (9a–b) with (8) above:

- (9)

- a.

- Ũn

- woman

- te=x

- ERG=1.SG

- penãhã

- see

- The woman saw me.

- b.

- *Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- ũg=penãhã

- 1.SG=see

- The woman saw me.

As for indirect speech, Popovich (1986) does not offer a formula but an example, shown here as (10). He states that indirect speech is rarely used:

- (10)

- Xukux

- aunt

- te

- ERG

- hãm’ãgtux

- say

- xa

- that-2

- mõg

- go

- Aunt said that you should go. (Popovich, 1986: 355)6

In comparing our data with Popovich’s, we found similarities to the structures in (5) and (6). Though we have not measured the frequency with which each of the structures occur, it seems that Popovich’s claim (Popovich 1986: 355) mentioned above is correct in that the strategy in (6) appears to be by far more frequent than that seen in (5b) both in spontaneous speech and in elicitations. Despite this, we were unable to find indirect quotation in spontaneous speech. Almost every instance of elicited quotation in Maxakalí was direct, even if the given form in Portuguese was in indirect speech. Consider the following sentences given to the speaker in Portuguese in indirect speech: “Juvenal said that this wood is strong and Paulinho said that it is revolver wood” and “Voninho asked Elismar if the house belongs to Elismar and Elismar said it wasn’t his”. The corresponding sentences obtained in Maxakali were:

- (11)

- Yomenãn

- Juvenal

- te

- ERG

- nũhũ

- this

- mĩm

- wood

- mai

- good

- xẽẽnnãg

- really

- ha

- and.DS

- Papnĩy

- Paulinho

- te

- ERG

- nõõm

- that

- hephot

- revolver

- mĩy

- make

- ax.

- NMZ

- Juvenal said that this wood is strong and Paulinho said that it is revolver wood.

- (Lit.: Juvenal (said): “This wood is really good” and Paulinho (said): “That is wood [for making a] revolver”.)

- (12)

- Toãyã

- brother.in.law

- Monĩ

- Voninho

- te

- ERG

- ã-pet

- 2-home

- õhõm?

- that

- ha

- and.DS

- Enixmã

- Elismar

- a

- NEG

- yõg

- my

- a.

- NEG

- Voninho asked Elismar if the house belongs to Elismar and Elismar said it wasn’t his.

- (Lit.: Brother-in-law Voninho (said): “Is that your home?” and Elismar (said): “It is not mine”.)

If in fact there really are only direct quoting constructions in Maxakalí, one should reanalyze Popovich’s example in (10) as follows:

- (13)

- Xukux

- aunt

- te

- ERG

- hãm’ãgtux

- tell

- xa

- 2.DAT

- mõ-Ø!

- go-IRR

- Aunt told you: “go!”

The reanalyzed example in (13) contrasts with the Maxakalí in (10) in two ways. Firstly, xa should be considered the addressee of the original speech event, rather than a second person purpose subordinate conjunction in Popovich’s description (1986: 354–355). Secondly, mõ, the irrealis form of mõg ‘go’, is the actually grammatical and attested form, as the quote is an order to the addressee.7

To provide additional evidence for this interpretation, we asked a Maxakalí consultant how he would say the equivalent of the following sentence in Portuguese: ‘The woman told you to go’. This sentence was provided as indirect speech, and we hoped he would thus give us an indirect quotation as well. The answer he provided, however, was in direct speech: Ũn te hãm’ãgtux xa: mõ! ‘The woman told you: “go!”’, just as in (13). This sentence confirms that the form xa ‘2.DAT’ corresponds to the addressee and therefore the verb in such a construction should be in the irrealis mood (mõ).

Verbs in the irrealis mood have no restrictions when occurring in quotes expressing orders or purpose clauses, which as mentioned before, are the two main contexts in which this mood is used. The sentence in (14) includes instances of both functions:

- (14)

- ta

- TOP

- axa

- HSY

- õm

- that

- te

- ERG

- nãy!

- wait.IMP

- ũ-xetut

- 3-wife

- ha

- to

- mõ-Ø

- go-IRR

- nũy

- PURP.SS

- xupa-x.

- listen-IRR

- And it is said that one said: “Wait! Go to his wife in order to listen (to her)”.

Inside the quote in (14) there are two verbs in the irrealis mood: mõ ‘go’ (whose realis form is mõg) and xupax ‘listen’ (whose realis form is xupak). The former is irrealis because it is an imperative, while the latter is irrealis because it is a purpose clause.

One may ask about whether the reanalyzed example in (13) includes a verb of speech (hãm’ãgtux). We must return to the structure in (5b): though infrequent, there is a type of construction in which there is a clear verb of speech. To verify if (5b) refers, in fact, to a direct quoting construction and not an indirect one, we present the example in (15):

- (15)

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- tut

- mother

- pu

- DAT

- hãm’ãgtux

- talk

- tu

- and.SS

- ũg=nãhã-Ø.

- 1.SG=fall-REAL

- The woman talked to her mother and (said): “I fell”.

This example provides morphosyntactic evidence that this is a direct speech structure. The quotation includes a first person singular marker, therefore denoting that the subject of the quoted sentence is the same as the main clause. Moreover, the conjunction tu exhibits same-subject switch reference morphology, indicating that the subject of both sentences is coreferential (Popovich 1986, n.d.; Pereira 2020).8

Additional evidence in favor of a direct quotation analysis is the presence of an interjection in the following sentence:

- (16)

- tu

- and.SS

- õm

- that

- hã

- INS

- mõxakux

- enter.PL

- tu

- and.SS

- Ak

- Ah

- nũhũ

- this

- mĩmtut

- house

- a

- NEG

- xũyã

- owner

- mai

- good

- a.

- NEG

- And they entered the house and (said): “Ah, the owner of this house is not good”.

The presence of the interjection ak ‘ah’ in the second clause of (16) strengthens the interpretation that the speech introduced by the conjunction tu in this example is direct rather than indirect, because interjections are not found in indirect speech, due to pragmatic reasons (Capone 2016: 62–65).

Although indirect speech as mentioned by Popovich was not generally found, we did document one indirect speech example from a Portuguese translation, registered during a grammar workshop we conducted in a Maxakalí village. It was considered grammatical by the speakers.

- (17)

- Mano

- Badô

- te

- ERG

- Yitmet

- Gilberto

- yĩkopit

- ask

- ya

- where

- mõ-g

- go-REAL

- mĩmtutmõg

- car

- hã

- INS

- ha

- and.DS

- Yitmet

- Gilberto

- te

- ERG

- hãm’ãgtux

- tell

- ũ-mõ-g

- 3-go-REAL

- apne

- village

- tu

- LOC

- nĩnãpa,

- up.there

- payã

- but

- putpu

- back

- nũ-n

- come-REAL

- nõyax.

- already

- Badô asked Gilberto where he goes by car and Gilberto said he goes to the village up there but will come back soon.

If the sentence (17) were direct speech, the first verb mõg would have included the second person marker ã-: “ya ãmõg mĩmtutmõg hã?” ‘Where are you going by car?’. Further evidence is found in the second clause where the verb mõg ‘go’ should have the form Ũg=mõg with the first-person singular clitic if it were direct speech. The present verbal form Ũ-mõ-g instead marks this speech as being indirect. The exceptionality of this construction is noteworthy, and unsurprisingly during that same workshop, another translation presented a related, more expected construction with direct speech:

- (18)

- Tik

- man

- te

- ERG

- ũn

- woman

- nua

- order

- pu

- 3.PURP.DS

- mãm

- fish

- geex

- fry

- ha

- and.DS

- tu

- 3

- te

- ERG

- hãm’ãgtux

- tell

- a

- NEG

- mãm

- fish

- ũm

- some

- pip

- be

- a.

- NEG

- The man told the woman to fry fish and she told him that there was no fish.

- (Lit.: The man ordered the woman in order for her to fry the fish and she said: “There is no fish”.

Therefore, we argue here that Maxakalí does not generally employ indirect speech, with the example in (17) being an exceptional case. (There may have been interference due to Portuguese being used as the elicitation language during the workshop.)

Within the current examples, the quoted clause acts as an argument within a null verb phrase. We argue that it is possible to recover the nature of this verb, and that it is in fact associated with the aforementioned optional element kaxĩy. Thus, the use of same subject switch-reference markers such as tu ‘and.SS’ and hu ‘CC.SS’ that accompany predicates do not trace the verb internally to the quote, but rather to a null external argument quoting verb.

The different markers in the structure in the formula in (5b) and the examples in (15–16) can be accounted for by the disparate semantic relations expressed by the conjunctions tu and hu. The former is found with coordinations of two clauses to indicate a temporal sequence of events, while the latter expresses a causal relationship between two clauses. In the examples so far, the conjunctions mark the same subject for both clauses, though this is not always the case, as illustrated in (19):

- (19)

- tui

- and.SS

- nũgtui

- coming.SS

- xetutj

- wife

- hã

- INS

- mõnãhã-Øi

- enter-SG-REAL

- yĩj

- CC.DS

- a

- NEG

- yã

- FOC

- yũmũgi+j

- 1.INCL

- penã

- see

- hok

- NEG

- a

- NEG

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- and (the man)i entered with the (other’s man)k wifej and (shej said): “(he)k is looking at usi+j”.9

The use of yĩ (the DS counterpart of hu) in (19), besides changing the subject from the man to the other man’s wife, also introduces the quotation by a different participant (the wife), with no overt verb of speech. In the example above, the use of yĩ rather than of ha (the DS counterpart of tu) implies that the married man is looking at his wife and that she warned the other man because (causal relation) she suspected her husband saw them entering the house.

To summarize, the evidence from a variety of phenomena, including switch reference marking, is consistent with our claim that Maxakali largely lacks indirect quotation.

5. Expressing thoughts and knowledge

Constructions that express thoughts are very similar to the direct quote formula expressed in (5b), but instead of using a verb of speech hãm’ãgtux, they employ the expression hãm pe pa xex ‘to think, to imagine’ (literally ‘to put the face on the side’):

- (20)

- Tik

- man

- te

- ERG

- hãm pe pa xex

- think

- hu

- CC.SS

- kakxop

- child

- yã

- FOC

- nãhã-Ø.

- fall-REAL

- The man thinks that the child fell.(Lit. The man put his face on the side and thus (thought) “The child fell”.)

There is another strategy to indicate thoughts and knowledge, restricted to the first person, using the particle ãmee. The expression hãm pe pa xex can be used for the first person as well: hãm pe=x pa xex, in which the allomorph =x of the clitic /=k/ refers to 1.SG.

The thoughts expressed with hãm pe pa xex are “direct” in nature in that they are, like direct speech, demonstrations and not descriptions. Examples (21) and (22) illustrate this:

- (21)

- Ũni

- woman

- te

- ERG

- hãm pe pa xex

- think

- hu

- CC.SS

- pa

- seem

- tikj

- man

- ãi

- 1.DAT

- hõm

- give

- mĩnnut.

- flower

- The woman thinks: “It seems that the man gave me a flower”.

- (22)

- Ũni

- woman

- te

- ERG

- hãm pe pa xex

- think

- ãmee

- 1.think

- kakxop

- child

- te

- ERG

- nõ

- 3.INS

- xupxet

- steal

- The woman thinks: “I think that the child stole it”.

The fact that the “quoted thought” of the woman in (21) has a first-person dative pronoun ã coreferential to the subject of the main clause Ũn ‘woman’ is an indicator that we are dealing with a “direct thought”. Likewise, the thought clause in (22) begins with ãmee, which can only be used to express the thought of the original speaker; thus, it can only be interpreted as a “direct thought” of the subject of the main clause, again Ũn ‘woman’.

Knowledge, on the other hand, is slightly different in that it is not “quoted”. Constructions with yũmũg ‘to know’ are genuine indirect propositions, as can be seen in (23):

- (23)

- a.

- Ũni

- woman

- te

- ERG

- yã

- FOC

- yũmũg

- know

- ũi-nãhã-Ø.

- 3-fall-REAL

- The womani knows that shei fell.

- b.

- Ũni

- woman

- te

- ERG

- yã

- FOC

- yũmũg

- know

- ũgj-nãhã-Ø.

- 1.SG-fall-REAL

- The womani knows that Ij fell.

The examples in (23) indicate that the complement of the verb yũmũg is another clause that is postposed to the verb. The referentiality relationship between the subject of the main clause and of the complement is different from the constructions we have seen thus far: in the case discussed here, the third-person marker in the complement clause is used to point to the third person subject of the main clause (23a) while the first-person marker in the complement is used to point to the speaker (23b).10

6. Ideophones, loan verbs, and transitivity

Ideophones and loaned verbs from Portuguese pattern differently from native verbs regarding argument marking that might be expected from intransitive verbs. Silva (2020) shows that these two groups of verbs always mark their subjects (A and S) with the ergative postposition te. Meanwhile, the “absolutive” argument (O) of the transitive ideophones and loan verbs are marked with the postposition hã, which is used elsewhere to either mark instrumental case or various kinds of adjuncts (such as location, manner, and temporal phrases). Below, we provide examples of both intransitive and transitive ideophones (24) and loan verbs (25). We indicate ideophones by using small caps, and also try to convey the ideophonic nature of those words by glossing them with English ideophones whenever we can find an equivalent:

- (24)

- a.

- Ã

- 1.SG

- te

- ERG

- PŨN.

- BOING

- I jumped. ~ I went BOING.

- b.

- Kutitta

- pineapple

- te

- ERG

- KẼM.

- strong.shade.of.red

- The pineapple is very red.

- c.

- Kokex

- dog

- te

- ERG

- kakxop

- child

- hã

- INS

- KANEP.

- CHOMP

- The dog bit the child. ~ The dog went CHOMP at the child.

- d.

- Ã

- 1.SG

- te

- ERG

- pa

- eye

- hã

- INS

- TŨG.

- SWISH

- I blinked my eye. ~ I went SWISH with my eye.

- (25)

- a.

- Nanuy

- orange

- te

- ERG

- takat

- expensive

- The oranges are expensive. (takat < Portuguese tá caro)

- b.

- Payã

- but

- tep

- what

- mũn

- just

- te

- ERG

- tapatãn?

- lack

- But which one is lacking? (tapatãn < Portuguese tá faltando)

- c.

- A

- NEG

- xa

- 2

- te

- ERG

- tãyũmak

- money

- hã

- INS

- pixiya

- need

- a.

- NEG

- You don’t need money. (pixiya < Portuguese precisar)

- d.

- Kõnããg

- water

- yã

- FOC

- tu

- 3

- te

- ERG

- mĩmãti

- rain.forest

- hã

- INS

- kunia

- create

- xi

- and

- yã

- FOC

- xokxop

- animals

- xohi

- many

- hã

- INS

- kunia.

- create

- The water created the forest and it created the animals. (kunia < Portuguese criar)

This pattern, which diverges from other intransitives seen above in fact follows the general patterning of native verbs: both ideophones and verbs loaned from Portuguese behave as quotations rather than as verbs.11 Before doing so, however, we must present some further data to strengthen our hypothesis that ideophones and loan “verbs” are distinct from actual native verbs.

While native verbs can undergo an alternation between short and long forms, ideophonic and loan verbs do not. Briefly, native verbs lengthen in the realis mood if their root ends in a vowel and if there are no modifiers after it. In the irrealis mood, only monosyllabic active verbs can lengthen, as they do not overtly express their SA argument. This lengthening, according to Silva (2020), occurs to satisfy the prosodic requirement of a phonological word to be at least two syllables long.

In example (26a), the active verb yũm appears in its short form, as it is in the realis mood and does not end in vowel. (26b), on the other hand, shows the long form of the verb yũhũm as it contains a (phonological) monosyllabic root of an active verb in the irrealis mood. In comparison, (27a) presents the long form of the inactive verb ti, as it ends in a vowel in the realis mood and is not followed by any modifier. Meanwhile, (27b) is in its short form because its SO argument must be expressed, thereby already fulfilling the minimum requirement of the ideal phonological word length of two syllables.

- (26)

- a.

- S-V

- Ã-yũm.

- 2-sit.SG

- You sit.

- b.

- SA

- Ø

- V

- Yũhũm!

- 2

- sit.SG

- Sit!

- (27)

- a.

- S-V

- Ã-tihi.

- 2-stand.PL

- You (PL) are standing.

- b.

- SO-V

- Ã-ti

- 2-stand.PL

- Stand!

- (28)

- a.

- Xa

- 2

- te

- ERG

- PŨN.

- BOING

- You jump. ~ You went BOING.

- b.

- Ø

- 2

- Pũn!

- BOING

- Jump! ~ Go BOING!

- c.

- *Ø

- 2

- PŨHŨN!

- BOING

- Jump! ~ Go BOING!

The onomatopoeic verb PŨN in (28), conversely, has only a “short” form both in realis mood, where it was not expected to lengthen anyway due to its root-final consonant, and also in the irrealis mood, where it is the only morpheme phonetically expressed, thus violating the two-syllable minimum size requirement that would be expected if it was a native verb.12

To further differentiate ideophones from verbs, let us recall what is said about them by Popovich (1986: 47, our emphasis), treating onomatopoeia and ideophones together. He says:

Onomatopoeic expressions are one word in length and are often repeated. They are introduced by the speech formula in the same way in which quotes are introduced, by pitch upglide and brief pause. Sound effects are accompanied by pitch glides or unusually low pitch….

His description thus equates ideophonic constructions with direct quoting, at least regarding intonation (see Section 4 above). But the similarities between those two constructions extend further. Consider example (29):

- (29)

- tu

- and.SS

- ta

- TOP

- mãm

- get.up

- ha

- and.DS

- YA

- BAM

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- and (Pukkutok) got up and (the larvae went) BAM!

In (29) we have an excerpt of a narrative in which Pukkutok (the Bee’s Child) is seated and counting larvae on his lap. When he realizes that there are few larvae, he stands up disappointed and lets the larvae fall with a ‘BAM!’. The structure is strikingly similar to those in (5–6) and those exemplified in section 4. There is no verb of speech (as it is not a speech quotation per se), but the clause with the ideophone is introduced by a switch reference conjunction ha and followed by kaxĩy.

The final difference between ideophones and other items of the native Maxakalí lexicon lies in their phonological structure. In addition to abstaining from the lengthening alternation seen in native verbs, it is common for ideophones in Maxakalí to be reduplicated (PŨN ~ PŨNPŨN ‘jump’ (BOING ~ BOINGBOING), GOXGOXGOX ‘zigzag’, and many others) and/or to have phonotactics that are otherwise rare. Nikulin & Silva (2020: 9–10) show the scarcity of syllables with a voiceless consonant followed by a nasal rhyme. In a 24-minute-long monologue containing 2288 words, these authors counted just 70 tokens of words with this structure, just 3% of the total words. Nonetheless, this syllabic structure is rather common in ideophonic words like the aforementioned PŨN ‘jump’, KẼM ‘have a strong shade of red’, TŨG ‘blink’, PÕGBÕG ‘swim’ ~ ‘SPLASH’, PÕYPÕY ‘have sex’, and many others. Aberrant sound combinations can be found in ideophones in Portuguese as well, for example NHAC ‘bite’, as words starting with a nasal palatal consonant (written as ⟨nh⟩) are rare; see also a similar description of phonotactic outliers for Xhosa ideophones (Andrason 2020). In summary, although voiceless consonants followed by nasal rhymes are generally rare in the Maxakalí lexicon, this phonotactic pattern is rather common in ideophones.

Bearing all this in mind, we argue that ideophonic verbs are not true Maxakalí verbs, but rather conventionalized or “frozen” quotes that express the actions described. As Clark & Gerrig (1990: 788–789) argue, conventional expressions of sound quotation (i.e., ideophones) are demonstrations in the same manner as direct quotations in that both provide depictive and supportive information: they highlight some aspects of the referent depicted (depictive aspects), as well as aspects that serve as a support to the demonstration performance that were not present in the original action. For example, a slow motion to show how one can serve a ball in a tennis match or how one can pretend to be holding a racket to depict such a serve (supportive aspects) (Clark & Gerrig 1990: 768).

Phonologically nativized loan verbs from Portuguese further demonstrate the exact same patterning as ideophones, though we do not have data in which they are followed by kaxĩy. The main evidence for loan verbs and ideophones constituting their own natural class of predicates is that they have a different syntactic alignment, and never undergo lengthening even if in a favorable context. Consequently, loan verbs from Portuguese should also not be treated as true verbs in Maxakalí but rather as quotations, in the same manner as laid out above for ideophones: both are demonstrations, and although they are intransitive predicates, they co-occur with ergative marking on the subject, consistent with the light verb analysis.

7. Is kaxĨy a quoting verb?

We now return to the question posed in Section 3 concerning the status of kaxĩy. Could it be a discourse marker indicating the end of the quote, a quotative verb due its final position in the sentences, or a mere adverb? Before providing an answer, we present some initial considerations. At first glance, this word could be interpreted as a verbal modifier akin to ‘like this’ in English, as it can be read in sentence (31) in a similar but not identical manner as the one in (7), repeated below as (30):

- (30)

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- kakxop

- child

- ũ-nãhã-Ø.

- 3-fall-REAL

- The woman said: “The child fell”.

- (31)

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- kakxop

- child

- ũ-nãhã-Ø

- 3-fall-REAL

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- The woman said: “The child fell”, like this.

In fact, there are several examples of kaxĩy that could be interpreted as ‘like this’ or ‘this way’ (assim in Portuguese), presented below:

- (32)

- Payã

- but

- xap

- sew

- hã

- INS

- kaxĩy

- this.way

- topixxax

- fabric

- But they sew the fabric like this.

- (33)

- Xi

- and

- kuhut

- cut

- hu

- cc.ss

- nõ

- 3.ins

- mõ=yãy=nĩy

- cover=refl=cover

- nõ

- 3.ins

- kaxĩy

- this.way

- And they cut (the fabric) and they covered themselves (with the pieces), like this.

- (34)

- Yũmũg?

- understand

- Kaxĩy!

- this.way

- Did you understand? Like this!

Kaxĩy also occurs in tandem with an argument marked by te (35), which leads us to suspect that kaxĩy is at least acting as a verb in this case. It is noteworthy that another formally and semantically related word, xĩy ‘how’, behaves identically to kaxĩy (36–38):

- (35)

- hãm

- time

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy

- this.way

- hã

- INS

- Yesterday (Lit.: At the time which was/happened this way)

- (36)

- Mãyõn

- sun

- te

- ERG

- xĩy?

- how

- What time is it? (Lit.: How is the sun?)

- (37)

- Tãyũmak

- money

- xohi

- many

- te

- ERG

- xĩy?

- how

- How much does it cost? (Lit.: How much money is it?)

- (38)

- Tu

- 3

- te

- ERG

- xĩy?

- how

- Why? (Lit.: How is it? / How did it happen?)

As we can see from examples (35–38), conventionalized constructions in Maxakalí using kaxĩy (and xĩy) are structured like sentences with transitive native verbs, or ideophonic and loan intransitive verbs in which the subject is marked with the postposition te and the object position is unfilled.13 The fact that kaxĩy and xĩy have parallel syntactic structures is unsurprising: they have phonological material in common as well as semantic correlates that describe the manner of the event. We postulate that kaxĩy is derived from xĩy, preceded by the prefix ka-, whose original function remains unknown as it is apparently no longer a productive affix.

Although it is possible for kaxĩy (and xĩy) to occur following an argument with the postposition te as in the preceding examples, its use without being involved in a quote is less common. It appears at times in conventional expressions as seen in examples (35–38) or in expressions headed by the instrumental postposition hã as shown in example (35), now repeated as (39):

- (39)

- hãm

- time

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy

- this.way

- hã

- INS

- Yesterday (Lit.: At the time which was/happened this way)

In this example, the whole clause hãm te kaxĩy is headed by the postposition hã. The resulting PP functions as a temporal adjunct, hãm te kaxĩy hã ‘yesterday’, suggesting that kaxĩy in this sentence is most likely a fossil within a larger construction. Further evidence that illuminates this assumption is the occurrence of this kind of construction with the temporal conjunction ĩhã (‘in this time’, ‘then’). This grammatical element often occurs when a temporal expression is included in the sentence:

- (40)

- hãmxip

- later

- ĩhã

- then

- Later (as an answer to an invitation to talk)

When a temporal expression with kaxĩy/xĩy is used in a larger sentence, the temporal marker ĩhã must be used:

- (41)

- Mãyõn

- sun

- te

- ERG

- xĩy

- how

- ĩhã

- then

- ũgmũg

- 1.EXCL

- mõ-g

- go-REAL

- ax

- FUT

- Ãnãtayit

- Anastasia

- hãm

- work

- ax

- NMZ

- tu?

- LOC

- At what time are we going to Anastasia’s land (literally ‘work place’)?

The co-occurrence of kaxĩy/xĩy with the temporal expression ĩhã establishes that kaxĩy/xĩy do not always function as free words, and in these cases are fossilized in word chunks. Despite this peculiar use of kaxĩy, it can also be found in more productive verbal uses as demonstrated by the examples (42a–b):

- (42)

- a.

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- ũg=mõ-g

- 1.SG-go-REAL

- kõmẽn

- city

- tu

- LOC

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- The woman (said): “I went to the city”, like this.

- b.

- Ũn

- woman

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- The woman (said) like this.

In (42a) we have a direct quote using the formula presented in (6) as discussed in the previous sections. In (42b), in contrast, the whole quote is suppressed while the structure of ‘Speaker te … kaxĩy’ is preserved. This is exactly the structure of a transitive native verb, specifically, the structure of an unergative verb: ‘A te [null object] verb’, which is quite common in Maxakalí:

- (43)

- xi

- and

- yã

- FOC

- hãmxop

- gift

- popmãhã,

- give.PL

- nẽnxõg

- sheet

- nõm

- that

- xexka

- big

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- and (they) gave (the ancestors) gifts, a sheet that was big like this.

- (44)

- Ã

- 1.SG

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy.

- this.way

- Ã

- 1.SG

- te

- ERG

- mĩ-y

- make-REAL

- nũhũ.

- this

- I (make) like this. I make this.

- (45)

- Yã

- FOC

- xohi

- many

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy,

- this.way

- yãmĩy

- spirit

- xop

- ASSOC

- yã

- FOC

- nũ-n

- come-REAL

- ax

- FUT

- nũy

- PURP.SS

- yũhũm.

- sit.SG

- Everybody does this way, the group of spirits will come to stay (in the village).

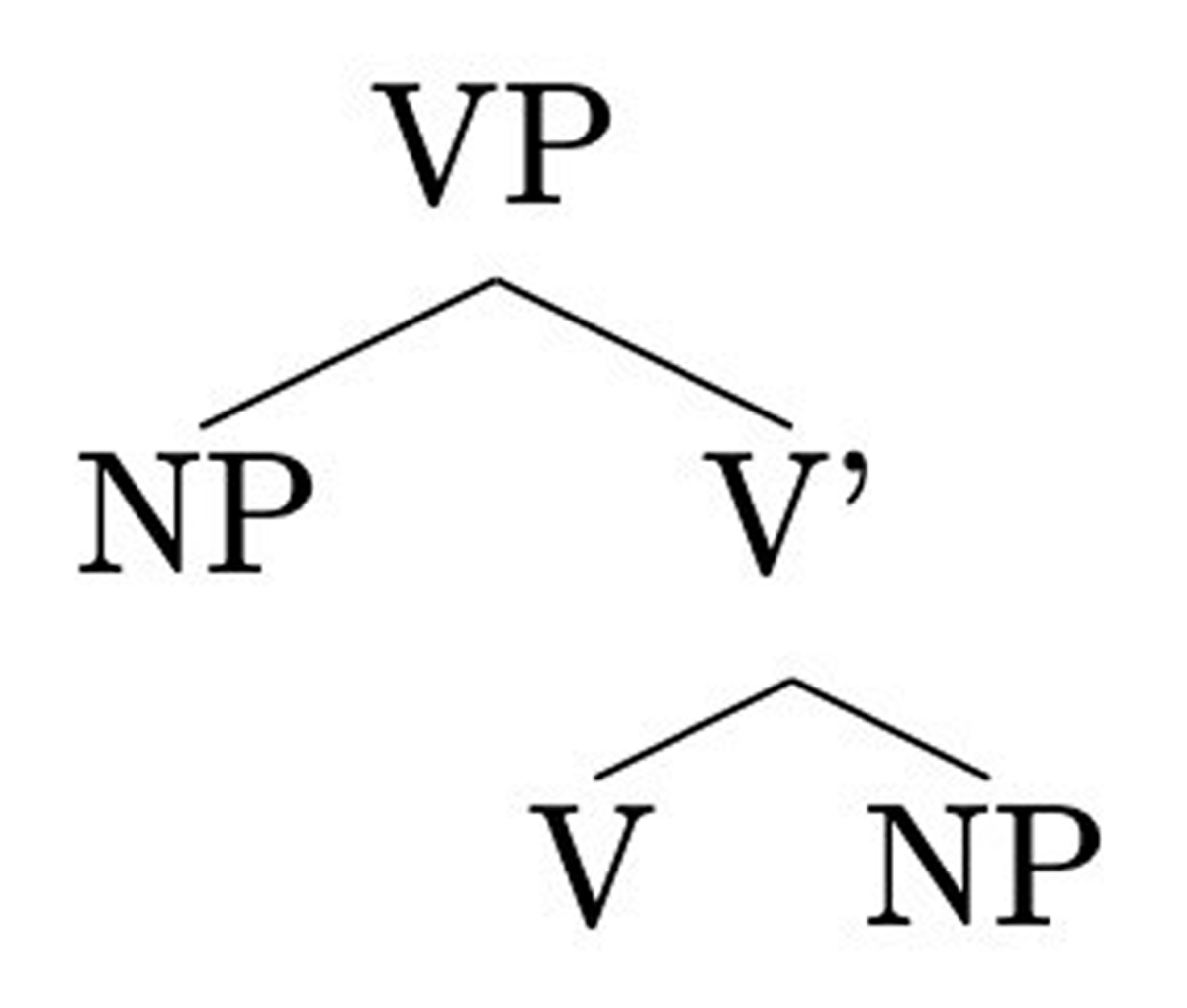

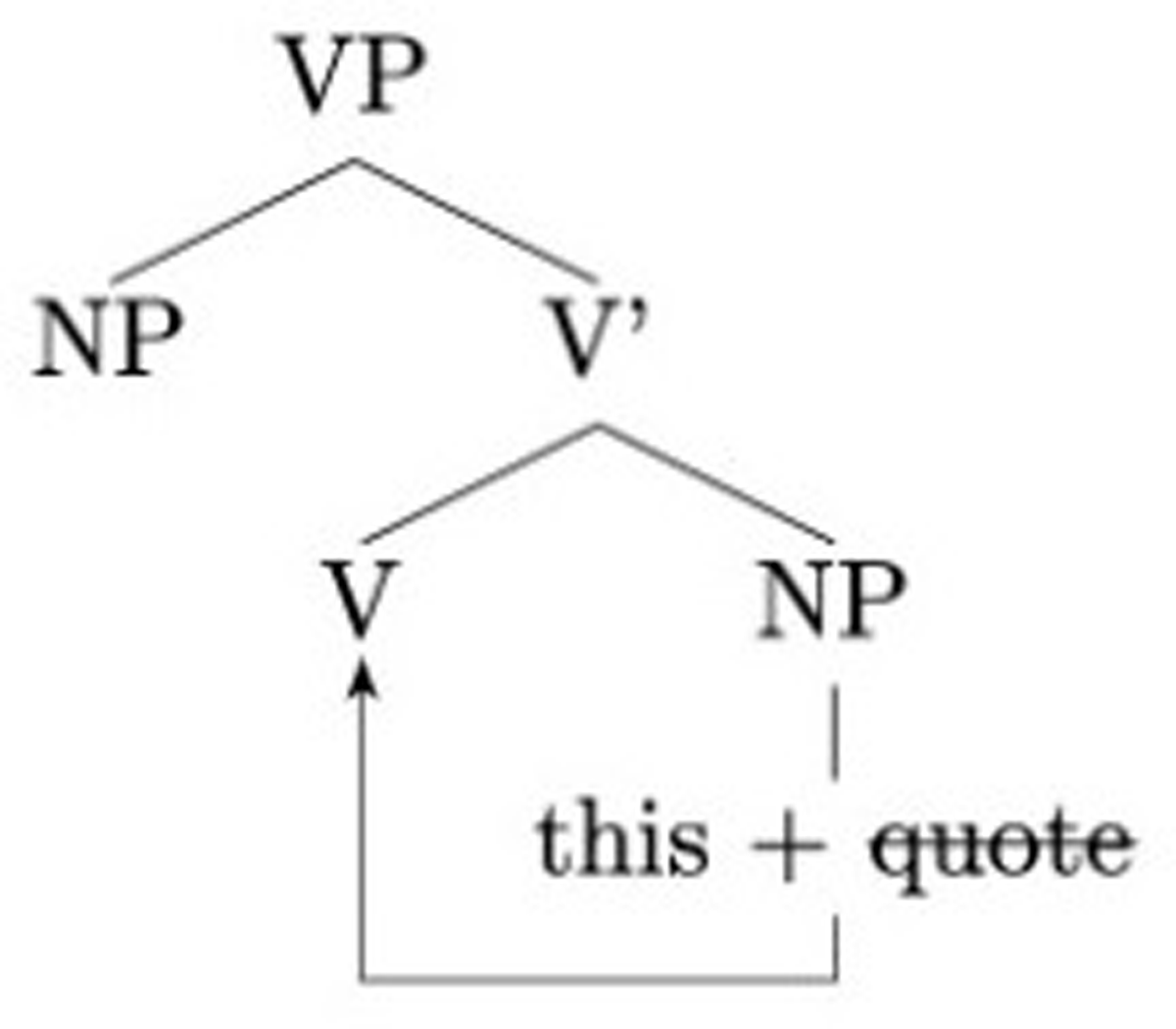

In (43–45), kaxĩy (meaning something like ‘do this way/like this’ or ‘make this way/like this’) seems to behave as an unergative verb, i.e., verbs that have an external argument headed by the postposition te and whose complement is a semantically incorporated object. In the specific case of kaxĩy, the quote itself would be the incorporated object. Unergative objects are incorporated through the process of conflation according to Hale & Keyser’s (1993, 2002) proposal. They use the term conflation for the situation in a transitive structure where a noun is incorporated into an empty light verb to form a denominal verb, together yielding unergative verbs (see Figure 2).14

Conflation, according to Hale & Keyser (1993: 73).

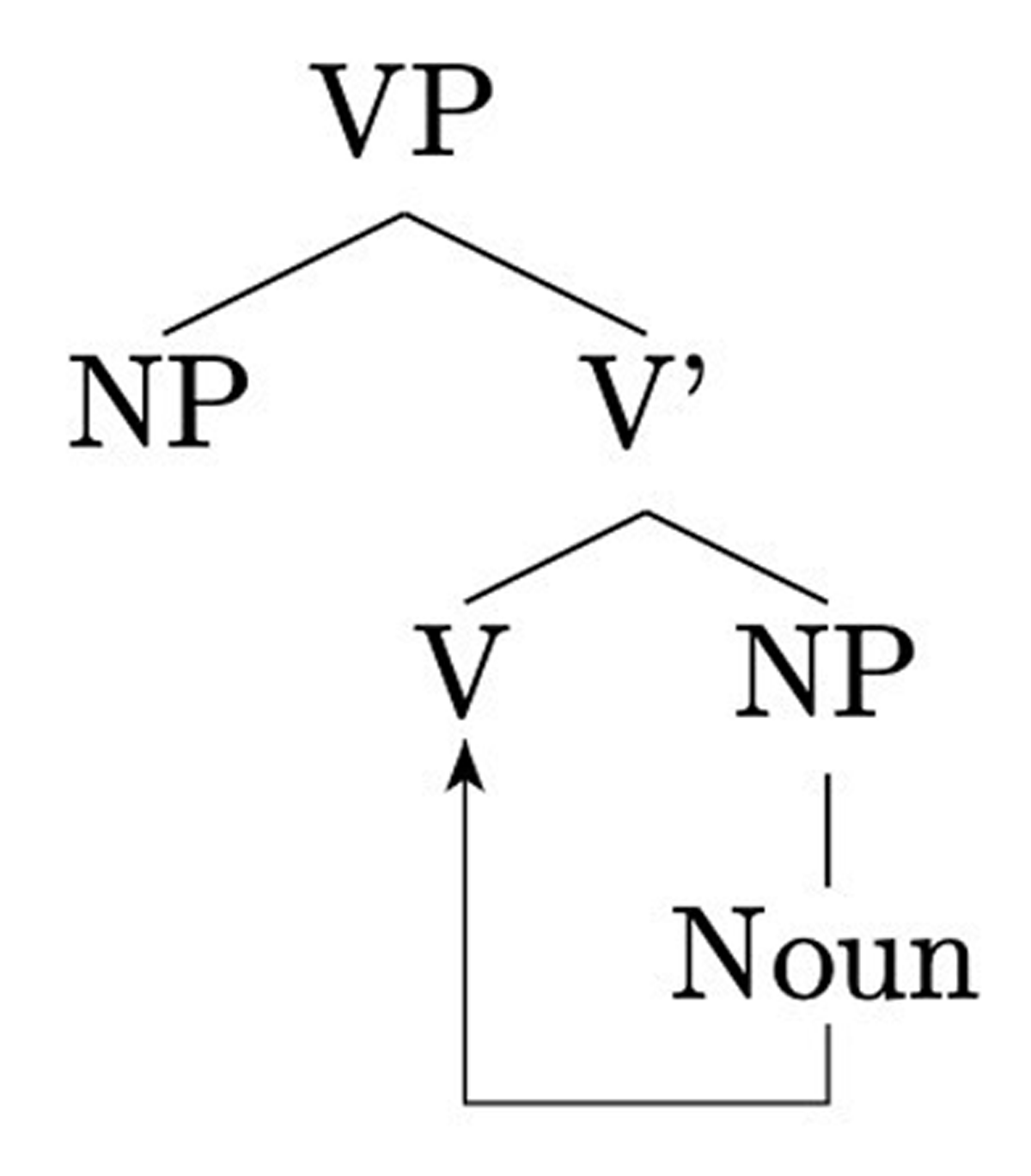

The unpronounced denominal complement incorporated into V would be the unergative verb as the tree notation shows:

In Figure 3, a noun is incorporated into V, yielding a typical unergative verb. So one could argue that kaxĩy is an unergative verb (at least in its version with a verbal reading) like ideophones, loan verbs, and some exceptional native verbs. Such an analysis was presented by Silva (2020; see also footnote 4). Although the quote is not a noun that could be incorporated and verbalized, one could assume that the whole quoted clause, meaning something as “it…”/“this…”/“that” (that was said) as a reference to the quote, would be incorporated into the light verb v, giving rise to a null verb of speech V meaning something like “to say X” (X would be the content of the quote) or “to say this” as shown in Figure 4:

As we can see in the tree representation in Figure 4, the quote or a null-reference to it as “this” is incorporated into V (and then verbalized as kaxĩy) due to the lack of an overt verb of speech.

There are other analytic possibilities, however. Although kaxĩy seems to share characteristics with unergative verbs in Maxakali, for example subjects headed by the postposition te and incorporated objects, there are also clear syntactic differences between unergatives and kaxĩy. The first of these dissimilarities is that kaxĩy is linked to the incorporated object, the quote itself. Although it is possible for kaxĩy to appear without a pronounced object (the incorporated quote or its correspondent “this”), the quote must be present either in a previous or in a following clause where kaxĩy occurs so that they can be bound. This binding of kaxĩy and its quote reference (“this”) can be observed in sentences (31) and (45), repeated here respectively as (46–47):

- (46)

- Ũn

- Woman

- te

- ERG

- [kakxop

- child

- ũ-nãhã-Ø]

- 3-fall-REAL

- kaxĩy

- this.way

- The woman said: “The child fell”, like this.

- (47)

- Yã

- FOC

- xohi

- many

- te

- ERG

- kaxĩy,

- this.way

- [yãmĩy

- spirit

- xop

- ASSOC

- yã

- FOC

- nũ-n

- come-REAL

- ax]

- FUT

- nũy

- PURP.SS

- yũhũm.

- sit.SG

- Everybody does this way, the group of spirits will come to stay (in the village).

In sentences (46–47), kaxĩy (in bold) is semantically bound to other constituents (delimited by square brackets). In (46), it is bound to kakxop Ũnãhã ‘the child fell’ in the preceding clause; in (47), it is bound to the quote yãmĩy xop yã nũn ax ‘the group of spirits will come’ in the following clause. This binding phenomenon is not present in unergative verbs, which do not have this co-reference with other elements in a sentence. Another mismatch between kaxĩy and unergatives is the absence of subjects related to kaxĩy with an agentive theta-role and the lowered pitch associated with kaxĩy compared with other verbs, including unergatives. This may weaken the argument that kaxĩy is an unergative verb, but it seems to correlate to the dicendi verb omitted in the quoted clause.

Despite these differences compared to unergatives, kaxĩy seems to be related to the light verb just like the unergatives. Since the direct object (the quote or its null-reference “this”) is associated into the light verb similarly to the unergative verbs, the function of kaxĩy would be to signal the complex quote/light verb construction in the sentence. More data must be gathered to fully tackle these questions. One still needs to determine if kaxĩy is a true quotative verb or a simple discourse marker. On the one hand, we found that kaxĩy fulfills the syntactic requirement of a transitive verb in Maxakalí, that is, it requires an external argument postposed by te, and appears canonically at the end of a sentence. On the other hand, quotes (and ideophones for that matter) can occur without kaxĩy, as demonstrated in the previous sections. Kaxĩy also has a distinct prosodic nature from the other verbs (see Figure 1), at least when used after quotations and ideophonic verbs.

We argue that on typological grounds that kaxĩy is indeed a verb but also that when used after quotations and ideophones, it is grammaticalized into a discourse marker that notes the way the said quotes/ideophones were performed. That is, kaxĩy, as a discourse marker, is used as a deictic to reinforce the demonstrative nature of the quote/ideophone and to highlight the connection between the quote and the null dicendi verb. Diessel (1999: 74) mentions that manner demonstratives can be used as discourse deictics and are often glossed as “in this/that way”, “like this/that”.

For example, in Tseltal, onomatopoeic ideophones involve a demonstration operator embedded under a reported speech predicate chi ‘say’ (Henderson 2016). And in Xhosa, sentences with ideophones require the verb thi, which “apart from its speech/sound related meaning, […] also communicates the set of meanings related to the idea ‘(do) like this, imitate’ [and] is often accompanied by a gesture or gesticulation.” Thus, the Xhosa verb thi derives either from a manner deictic (focal) element ‘thus, like this’ or from a generic action verb. Finally, it is important to note that the presence of Xhosa thi is not compulsory. In several cases, this verb is (or may be) omitted and, further, it is phonetically eroding through gradual change (Andrason 2018).

We therefore analyze kaxĩy, when present in quoting/ideophonic constructions, as a demonstration operator grammaticalized from the verb kaxĩy ‘to be this way/like this’. This conclusion is arrived at because of the unusual features of kaxĩy for a verb (optionality and different prosody). Unlike in Tseltal, the presence of the operator in Maxakalí is optional.

The verb in quoting constructions is null, but its presence can be apprehended from the operator kaxĩy. We posit this null verb considering that, as said before, kaxĩy is not a quoting verb and from the fact that in other languages, as it is the case in Xhosa, the dicendi verb may phonetically erode. If our hypothesis is correct, the verb in Maxakalí has eroded completely but can be recognized from both the argument structure ([A te quotation]) and the presence of kaxĩy. This can be summarized with the formula in (48) and illustrated in the example in (49):

- (48)

- Speaker te quote null.dicendi.verb (kaxĩy)

- (49)

- [ũn

- woman

- te]A

- ERG

- [kakxop

- Child

- ũ-nãhã-Ø]O

- 3-fall-REAL

- [Ø]V

- null.verb

- [kaxĩy.]OPERATOR

- this.way

- The woman said: “The child fell”, like this.

In the sentence in (49) above, there is a null dicendi verb that is transitive in nature, derived from the fact that it has an argument (A) that indicates the speaker and is syntactically marked by te and an argument (O) that is an unmarked clause. Kaxĩy, because of its nature in this kind of construction, cannot be considered a verb but rather a modifier/operator to the null dicendi verb. Its position on the right of the verb is due to verbal modifiers in Maxakalí often being placed after rather than before the verb. This may indicate that kaxĩy has an adverbial status due to its relative fixed position near the verb. Adverbs, which have lower positions (VP-Adverbs), are involved in the modification of the verbal predicate (Predicate Operators) in opposition to Propositional Operators or S-Adverbs (Cinque 1999; Jackendoff 1972), as seems to happen with kaxĩy when it takes scope over the predicate involved in the demonstration.

We have thus seen that kaxĩy is typically used in three ways: (1) as a verbal modifier following the quote, translated as “this way” or “like this” (as in 31–34); (2) as a verb in conjunction with an argument marked by te in fossilized expressions (as in 35–38); and (3) in prototypical verbal uses with an argument marked by te (as in 42–45).

More tests to verify the status of kaxĩy must be undertaken. One possible test is to check if quotations with other verbal modifiers such as mai ‘good/well’, tix ‘twice’, or hok ‘prohibitive’ are grammatical. That is, one should examine the structure of sentences like ‘He said X well’, ‘He said X twice’, and ‘Do not say X!’: if similar to the structure in (48) but with other modifers being used instead of kaxĩy, then it would support the analysis as a modifier.

8. Conclusions and open questions

In this paper we examined quoted speech in Maxakalí and a related phenomenon, the use of the expression hãm pe pa xex ‘to think’. We showed that although Maxakalí has been described as having both direct and indirect quotation, indirect quotation is absent in spontaneous speech, indicating that Maxakalí does not have indirect speech, pace Popovich (1986). Direct speech is introduced by means of kaxĩy used in three different possible ways: as a verbal modifier and as a verb in typical verbal uses or in fossilized expressions. We described the use of ideophones and loan verbs from Portuguese and showed that both are not treated as true verbs in Maxakalí, but rather more akin to quotations, with a null light dicendi verb.

Though we now have a broader understanding of kaxĩy and its various functions, more investigation needs to pursued in order to better understand its idiosyncratic behavior. Its status as a verb modifier with the function of a demonstration operator in quotations should be confirmed, alongside investigating whether its distinct prosodic pattern is due to a grammaticalization process, or additional factors.

Notes

- In this paper, we write the examples with the orthography used by the Maxakalí communities. The graphemes ⟨p, t, x, k⟩ represent the voiceless stops /p, t, c, k/. ⟨m, n, y, g⟩ are used to represent the voiced stops /b, d, ɟ, ɡ/ and their nasal allophones, respectively [m, n, ɲ, ŋ]. Two other consonantal graphemes are ⟨h, ‘⟩ which are used to represent /h/ and /ʔ/. This last segment is not considered as a phoneme by Silva (2020) but has phonological status for Gudschinsky, Popovich, & Popovich (1970), Wetzels (1993, 1995, 2009), Wetzels & Sluyters (1995), Araújo (2000), and Campos (2009). The presence or absence of ⟨’⟩ in writing varies with individual preference. Oral vowels /i, ɨ, u~o, ɛ, a/ are written as ⟨i, u, o, e, a⟩ and their nasal counterparts are written with a tilde above them: ⟨ĩ, Ũ, õ, ẽ, ã⟩. In addition, we employ three symbols not used in Maxakalí orthography: the hyphen ⟨–⟩ to indicate morpheme boundaries inside a word, the equals sign ⟨=⟩ to indicate clitic boundaries to their hosts, and the symbol ⟨Ø⟩ to indicate a zero-morpheme. We also use, in some examples, the subscript letters ⟨i, j, k⟩ for indicating coreferentiality, and an asterisk ⟨*⟩ for indicating ungrammatical sentences. [^]

- The glossing conventions used within this paper are: 1 first person; 2 second person; 3 third person; CC cause and consequence relation; DAT dative; DS different subject; ERG ergative; EXCL exclusive plural; FOC focus; FUT future; HSY hearsay; IMP imperative; INCL inclusive plural; INS instrumental; IRR irrealis mood; LOC locative; NEG negation; NMZ nominalizer; PURP purpose; PL plural; REAL realis mood; REFL reflexive; SG singular; SS same subject; TOP topic change. [^]

- According to Campos (2009), Maxakali is morphosyntactically a tripartite language, distinguishing arguments A, So, and O. [^]

- According to Silva (2020), there are four exceptions in which the subject of an apparent intransitive verb is marked with te: tatxok ‘to bathe’, hãmyãg ‘to dance’, xupxet ‘to steal’, and kaxĩy ‘to be this way/like this’. There is evidence, however, that the number of unergative verbs in Maxakalí may be higher. On this last verb—crucial for the understanding of quoting in Maxakalí—see Sections 4, 6, and 7. Verbs loaned from Portuguese and ideophonic verbs pattern differently from native ones, as discussed in Section 6. [^]

- The 1.SG marker is a clitic. According to Silva (2020: 230–242), it has an underlying form of /=k/ and selects as its host the word on its left if it ends in a vowel. If this vowel is front, palatalization occurs and thus it is realized as a coda [j] (orthographically written aS ⟨x⟩). In case that the clitic is preceded by a consonant, by silence, or by a different clause (as in (8)), it attaches to a host on its right. In this case, it is still syllabified as a coda consonant, as it is preceded by an epenthetic nasal vowel /ɨ̃/ and then undergoes nasalization, being represented orthographically as Ũg. Here we represent these allomorphs according to the widespread orthographic usage in the community. [^]

- We have adapted the orthography in the example to better reflect the writing practices of the Maxakalí, rather than the usage by Popovich. The glossing of te has also been adapted in order to fit the glossing of the rest of the paper. In addition, the use of orthographic space in complex words varies among written texts. One specific example worth mentioning here is the morphologically complex sequence hãm’ãgtux. This is a morphologically complex item, hãm=ã-gtux, but we do not indicate this in the gloss, since it is not relevant to the questions treated in this paper. The clitic hãm= has two functions; the one here serves to change a relational lexeme (that is, which obligatorily has an internal argument) to an absolute one (that does not need an internal argument). In this example, it serves as a placeholder for the internal argument, with a pronoun-like function. The second morpheme ã- indicates that the verb has not moved away from its internal argument (in this case hãm=) for prosodic considerations; that is, the internal argument is just adjacent to the verb’s left margin (Silva 2020: 242-244). Finally -gtux is the root for ‘say/tell’. [^]

- Here we must take into consideration the somewhat irregular inclusion of syllable codas in Popovich’s works (cf. Silva 2020: 152), which would explain the different forms and consequently the different moods in the glosses (realis vs. irrealis). [^]

- In this regard it is important to mention that, in a switch reference construction, the portion (speaker + te) in the quoting formula presented in (6) should be replaced by a conjunction that may or may not be coreferent with the subject of the main clause. As we will show, different conjunctions appear in these situations in the data. [^]

- Negation in Maxakalí is usually realized by a circummorpheme a … a (Campos 2009: 128–130; Silva 2020: 265–268). Hok also is a morpheme with negative semantics, but with other functions that are still not fully clear, one being a polite prohibitive marker (Campos 2009: 123–128; Silva 2020: 268–269). The double negative a … hok a yields a positive statement (i.e., one negative cancels the other one), as in the example above. [^]

- In that sense, the verb yũmũg behaves just like perception verbs such as penãhã ‘see’ and xupak ‘listen’ such as in (i) and (ii) below:

- (i)

- Ã

- 1.SG

- te

- ERG

- penãhã

- see

- tik

- man

- te

- ERG

- pox

- arrow

- hĩy.

- tie.up.SG

- ‘I saw the man tie up the arrow.’

[^]- (ii)

- Tu

- 3

- te

- ERG

- xupa-k

- listen-REAL

- Ũn

- woman

- te=x

- ERG=1.SG

- mãnõg

- scold

- ‘He listened to the woman scolding me.’

- Native verbs have an ergative alignment in realis mood (A≠S=O), with a split in irrealis mood (SA≠SO=O) and ideophones and loan verbs have an apparently nominative alignment (A=S≠O). Examples (14) and (21) include verbs in the irrealis mood, thus showing this kind of split (see Silva 2020). [^]

- Onomatopoeiae form a subclass of ideophones. While the larger group comprise words that broadly evoke sensory impressions, onomatopoeiae are more restricted, as they depict only sounds. Even though most ideophones in Maxakalí are onomatopoeiae, there are some of them that do not necessarily indicate sounds, such as GOXGOXGOX ‘zigzag’, KANEP ‘bite’ ~ ‘CHOMP’, KẼM ‘have a strong shade of red’, and XÃG ‘darken’, among others. [^]

- We consider all verbs with an external argument to be transitive, on the assumption that transitive verbs may have a semantically incorporated object (Hale & Keyser 1993). [^]

- Hale & Keyser’s (1993) light verb V has been subsequently replaced in much literature by the notion of a light v projection above VP itself (which in turn can condition the presence of ergative marking on the subject). For the purposes of discussion here, we maintain the original proposal with conflation into V. [^]

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the Maxakalí people for always welcoming us in their villages and for all the years of research collaboration. We would also like to thank Suzi Lima and Tonjes Veenstra for the opportunity to take part in the “Speech and attitude reports in Brazilian languages” project, to Françoise Rose, to Sara Hockett, and to all participants who commented and shared their insights with us at the project workshop in Belém in December 2019.

Funding Information

Some of the data for this paper was collected in a field trip funded by the COSY Project (DFG-GZ:SA 925/14-1), Leibniz-Zentrum Allgemeine Sprachwissenshaft Berlin.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Andrason, Alexander. 2018. Ideophones as linguistic “rebels”: The extra-systematicity of ideophones in Xhosa (part II). Manuscript.

2 Andrason, Alexander. 2020. Ideophones as linguistic “rebels”: The extra-systematicity of ideophones in Xhosa (part I). Asian and African Studies (Slovak Academy of Sciences) 29(2): 119–165.

3 Araújo, Gabriel A. 2000. Fonologia e morfologia da língua Maxakalí [Phonology and morphology of the Maxakalí language]. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas masters thesis.

4 Campos, Carlo S. O. 2009. Morfofonêmica e morfossintaxe do Maxakalí [Morphophonemics and morphosyntax of Maxakalí]. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais doctoral thesis.

5 Capone, Alessandro. 2016. The pragmatics of indirect reports: Socio-philosophical considerations (Perspectives in Pragmatics, Philosophy & Psychology 8). Cham: Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41078-4

6 Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads. New York: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195115260.001.0001

7 Clark, Herbert H. & Richard J. Gerrig. 1990. Quotations as demonstrations. Language 66(4): 764–805. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/414729

8 Diessel, Holger. 1999. Demonstratives, forms, functions and grammaticalization (Typological Studies in Language 42). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/tsl.42

9 Gudschinsky, Sarah C., Harold Popovich & Frances Popovich. 1970. Native reaction and phonetic similarity in Maxakali phonology. Language 46(1): 77–88. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/412408

10 Hale, Ken & Samuel J. Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. In Ken Hale & Samuel J. Keyser (eds.), The view from Building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, 53–109: Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

11 Hale, Ken & Samuel J. Keyser. 2002. Prolegomenon to a theory of argument structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5634.001.0001

12 Henderson, Robert. 2016. A demonstration-based account of (pluractional) ideophones. Proceedings of SALT 26: 664–683. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v26i0.3786

13 Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

14 Nikulin, Andrey. 2020. Proto-Macro-Jê: Um estudo reconstrutivo [Proto-Macro-Jê: A reconstructive study]. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília doctoral thesis.

15 Nikulin, Andrey & Mário A. C. da Silva. 2020. As línguas Maxakalí e Krenák dentro do tronco Macro-Jê [The Maxakalí and Krenák languages within Macro-Jê stock]. Cadernos de Etnolinguística 8(1): 1–64.

16 Pereira, Sílvia S. 2020. Switch reference in Maxakalí. In Marcelo Silveira, Maria J. G. F. Garcia & Ludoviko C. dos Santos (eds.), Macro-Jê: Língua, cultura e reflexões. Londrina: EDUEL.

17 Popovich, Harold. 1985. Discourse phonology of Maxakalí: A multilevel, multiunit approach. Arlington: University of Texas doctoral thesis.

18 Popovich, Harold. 1986. The nominal reference system of Maxakali. In Ursula Wiesemann (ed.), Pronominal systems, 351–358: Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

19 Popovich, Harold. n.d. Conjunções em Maxakalí [Conjunctions in Maxakalí]. Manuscript.

20 Rodrigues, Aryon D. 1999. Macro-Jê. In Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald & R. M. W. Dixon (eds.), The Amazonian languages, 164–206 (Cambridge Language Surveys). Cambridge: Press.

21 SIASI – Sistema de Informação da Atenção à Saúde Indígena. 2014. Dados populacionais indígenas por diversos parâmetros de análise [Indigenous population data by diverse parameters of analysis]. Online at http://portalsaude.saude.gov.br/index.php/o-ministerio/principal/leia-mais-o-ministerio/70-sesai/9518-siasi

22 Silva, Mário A. C. 2020. Tikmũũn yĩy ax tinã xohi xi xahĩnãg – Sons e pedaços da língua Maxakalí: Descrição da fonologia e morfologia de uma língua Macro-Jê [Sounds and pieces of the Maxakalí language: A description of the phonology and morphology of a Macro-Jê language]. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais doctoral thesis.

23 Wetzels, Willem L. 1993. Prevowels in Maxacali: Where they come from. Boletim da Associação Brasileira de Lingüística 14: 39–63.

24 Wetzels, Willem L. 1995. Oclusivas intrusivas em Maxacalí [Intrusive stops in Maxakalí]. In Willem L. Wetzels (ed.), Estudos fonológicos das línguas indígenas brasileiras, 85–102: Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ.

25 Wetzels, Willem L. 2009. Nasal harmony and the representation of nasality in Maxakali: Evidence from Portuguese loans. In Andrea Calabrese & Willem L. Wetzels (eds.), Loan phonology, 241–270 (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 307). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.307.11wet

26 Wetzels, Willem L. & Willebrord Sluyters. 1995. Formação de raiz, formação de glide e ‘decrowding’ fonético em Maxacalí [Root formation, glide formation, and phonetic decrowding in Maxakalí]. In Willem L. Wetzels (ed.), Estudos fonológicos das línguas indígenas brasileiras, 103–149. Rio de Janeiro: Editora UFRJ.