1 Introduction

This paper presents a series of grammatical phenomena connected with quote constructions in Panará, a Northern Jê language spoken in central Brazil. Quote constructions encompass a wide variety of syntactic strategies that a language can use for quoting both direct and indirect speech. In the case of Panará, discussing quotation means also discussing clause type and the structure of the polysynthetic verbal complex. Unless otherwise indicated, the data presented were collected by the author over the course of several fieldwork stays among the Panará since 2014.

2 The Panará language

Panará is the language spoken by the members of the Indigenous nation also called Panará, from the autonym /panãra/ ‘those that are’. Panará today has over 600 speakers who live in the officially demarcated Panará Indigenous Land on the Iriri and Ipiranga rivers. Today the Panará land is a territory of 500,000 hectares across the state border between Mato Grosso and Pará in central Brazil. However, until the 1970s their territory was much larger, occupying an area between the Cachimbo mountain range and the modern city of Sinop in several village clusters.

The Panará were eventually reduced to less than 10% of their population as a result of their first contact with neocolonial Brazilian society, when they contracted highly contagious diseases from the Brazilian government’s contact expedition and the workers that were building the BR-163 highway, which would connect Cuiabá and Santarém, across Panará land. In 1974, the 67 survivors were forcibly removed from their land and relocated to the Xingu Indigenous Park. Twenty years later, in the 1990s, they were successful in their lengthy fight to demarcate a piece of their land that still contained Amazonian rainforest and were able to move back. Since then, they have seen a demographic and social expansion and now occupy seven different villages.

Panará was classified as a Jê language following an initial hypothesis presented by Heelas (1979) that established the correspondences between their language and a series of word lists collected from a supposedly extinct Jê group that lived further south in Brazil in the 18th and 19th centuries, called the Southern Cayapó by colonists (Giraldin 1997). Linguistic work by Rodrigues and Dourado (1993) later proved that Panará is indeed a Jê language (Davis 1966), in the Macro-Jê macro-family. Since then, Panará has been classified as a Northern Jê language alongside Apinajé, Kajkwakratxi, Kĩsêdjê, Mẽbêngôkre, and the Timbira languages (Rodrigues 1999).1

The Panará polysynthetic verb complex presents morphological cross-reference with all kinds of arguments. For the sake of ease in examining the examples provided throughout the paper, the paradigms of argument cross-reference are included in Table 1. As the paradigms in Table 1 show, the irrealis portion of the reality status dimension of Panará presents a tripartite alignment in its argument cross-reference; rather than the ergative-absolutive pattern that argument clitics display in realis, in irrealis there is a different cross-reference for the ergative, for the transitive absolutive, and for the intransitive absolutive.

Panará argument clitics.

| erg | abs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sg | pl | sg | pl | ||||

| real | 1 | rê | nẽ~rê | ra | ra | ||

| 2 | ka | ka rê | a | rê a | |||

| 3 | ti | nẽ~rê | Ø | ra | |||

| abstr | absintr | ||||||

| sg | pl | sg | pl | sg | pl | ||

| irr | 1 | Ø | Ø | ra | ra | Ø Ø | Ø Ø |

| 2 | ti | ti rê | a | rê a | ti a | ti rê a | |

| 3 | ti | ti | Ø | ra | ti Ø | ti Ø | |

At the same time, as Table 1 shows, there is an impoverished morpheme inventory for the exponence of person features in the irrealis, with multiple exponence for intransitive absolutives, as illustrated in examples (1) to (3). To reflect the distinction between irrealis 1st person /Ø/ against 2nd + 3rd person /ti/, on the one hand, and 2nd person /a/ against 1st + 3rd person /Ø/, on the other, I gloss the irrealis ergative and intransitive absolutive clitics as spk ‘speaker’ and nspk ‘non-speaker’ on the left slot, and adre ‘addressee’ and nadre ‘non-addressee’ on the right slot, closest to the verb.2

- (1)

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- spk

- py=

- iter

- Ø=

- nadre

- pôô

- arrive

- I will come back.

- (2)

- ka=

- irr

- ti=

- nspk

- py=

- iter

- a=

- adre

- pôô

- arrive

- You will come back.

- (3)

- ka=

- irr

- ti=

- nspk

- py=

- iter

- Ø=

- nadre

- pôô

- arrive

- He/she will come back.

Panará presents several syntactic differences from the other Jê languages, not only in the Northern branch but also elsewhere in the family, all of which are arguably innovations (Bardagil 2018; Dourado 2001). Notably, Panará lacks the templatic Jê verb-final clause structure with fixed case positions seen in (4) for Mẽbêngôkre. Instead, in Panará the Jê verb-final clause was reanalyzed as a polysynthetic verbal complex with a series of proclitics, as can be seen in (5). Panará participant clitics present discontinuous exponence, some are omittable, and some are homophonous with free pronouns. They also present omnivorous number, with a single number morpheme controlling more than one argument, in this case the dual clitic (Bardagil 2020). Person-case restrictions are also manifested in Panará, as a ban on the co-occurrence of 1st and 2nd absolutive and dative clitics (Bardagil 2019).

- (4)

- Mẽbêngôkre

- ba

- 1sg.top

- nẽ

- nfut

- ba

- 1sg.nom

- ari

- pl

- kot

- com

- i=

- 1sg.abs

- tẽ

- leave

- mã

- away

- I went away with them.

- (5)

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- jy=

- intr

- py=

- dir

- ra=

- 3pl

- kõ=

- com

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- tẽ

- leave

- mãra-mẽra

- 3sg-pl

- kõ

- com

- I went away with them.

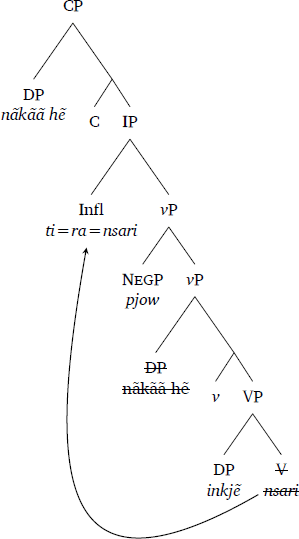

In Panará, rather than the verb remaining in a low VP-internal position as elsewhere in the family, the verb raises to Infl, which is also the cliticizing category. This results in the language’s non-verb-final constituent order (6), with the syntactic derivation illustrated in (7).

- (6)

- nãkãã

- snake

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- nsari

- bite

- pjow

- neg

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- The snake didn’t bite me.

- (7)

Unlike in the other nine Jê languages, Panará arguments always receive ergative-absolutive case marking. This has a direct connection with clause typology in the languages of the Jê family. In main clauses, the Jê verb typically appears in a short form and the case marking is nominative-accusative—with a further split intransitive distinction between unergative and unaccusative verbs. In order to build subordinate clauses, however, Jê languages require a nominalized verb, in which the case marking switches to ergative-absolutive. This is exemplified in (8) for Kĩsêdjê.

- (8)

- Kĩsêdjê

- hẽn

- fact

- Ø

- 3sg.nom

- [i=

- 1sg.nom

- nã

- mother

- {re/ra

- erg

- /*Ø}

- nom

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- khuru ]

- eat.lg

- khãm

- ines

- s=

- 3sg.abs

- õmu

- see.sh

- He/she saw my mother eating. (Nonato 2014: 104)

Just like in the other Jê languages, Panará subordinate clauses are head-internal. In contrast to the classic Jê pattern, however, they show all the properties of finite main clauses with respect to their argument marking, modal morphology, case marking alignment, and available left periphery (9).

- (9)

- [Patty

- Patty

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pĩra

- kill

- swasĩrã]

- peccary

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- ku= krẽ

- chew= eat

- I ate the peccary that Patty killed.

In sister languages to Panará in the Northern Jê branch, embedded clauses are characterized for the lack of finiteness and an unavailability of clausal positions higher than Infl (Bardagil 2018; Bardagil & Groothuis 2023; Salanova 2007). This is not the case for Panará, which can have its anchoring TAME category, i.e., reality status or mood, manifestly present in embedded contexts, such as relative and dependent clauses, denoted by square brackets through examples, including (10–11).3

- (10)

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- s=

- 3sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- [ ippẽ

- non-Indigenous

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pẽẽ ]

- speak

- I saw the white man who spoke.

- (11)

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- s=

- 3sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- [ ippẽ

- non-indigenous

- ka=

- irr

- ti=

- nspk

- Ø=

- nadre

- pẽẽ ]

- speak

- I saw the white man who will speak.

Relativization is available to all argument types (12–13). Relativization, and clause embedding more generally, is not sensitive to constraints on classes of arguments, such as syntactic ergativity, and all types of arguments can head an embedded clause.

- (12)

- Intransitive absolutive

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sõti

- sleep

- [ inkjêê

- woman

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pôô ]

- come

- The woman that arrived is sleeping.

- (13)

- Ergative

- [ toopytun

- old-man

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pĩri

- kill

- swasĩra ]

- peccary

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- junpjâ

- father

- hẽ

- erg

- The old man that killed a peccary is my father.

- (14)

- Transitive absolutive

- [ ka

- 2sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ka=

- 2sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pĩri

- kill

- swasĩra

- peccary

- ka

- 2sg

- sipjâ

- wife

- mã ]

- dat

- nãsisi

- sweet

- The peccary you killed for your wife was tasty.

The same properties seen for relative clauses hold for complement clauses. The case marking is ergative-absolutive, the constituent order is free, and both the pre- and postverbal positions inside the clause are available (15).

- (15)

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- s=

- 3sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- [ joopy

- jaguar

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pĩri

- kill

- kôôtita ]

- chicken

- I saw the jaguar killing a chicken.

Having established the relevant morphosyntactic characteristics of Panará, the rest of this article is devoted to Panará quotation strategies.

3 Panará quotation strategies

Panará employs a wide range of syntactic strategies to indicate quotation. This section presents Panará direct and indirect quotes, and also a particular type of quotes that appear in narration contexts, which I call here narrative quotes. In what follows I describe each type of quote and the grammatical cues that signal the different types.

3.1 Direct and indirect quotations

Before looking at the properties of the quote constructions present in Panará, I will lay out the basic characteristics of the two types of quotations, direct and indirect. Quotations are a grammatical mechanism to convey in a conversation an illocution that someone has said previously, or that someone will say in the future. Direct quotations are a type of demonstration (Clark & Gerrig 1990: 756), the linguistic version of the way in which one would depict any action being demonstrated, whether linguistic or not, as in (16).

- (16)

- a.

- And she went “Bye, I’m leaving!”

- b.

- And she went <waving hand gesture>.

This distinguishes direct quotations from indirect quotations, which are not demonstrations but descriptions (Clark & Gerrig 1990: 764), as presented by the speaker from their perspective, as in (17).

- (17)

- And she said that she was leaving.

In Panará, a direct quotation is a demonstration of an illocutive act that was or will be said. It is typically the complement of a verb of saying, as in (18), but it can also be introduced elliptically by just indicating the speaker, such as the ergative argument in (19).

- (18)

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- prẽ

- who

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- too

- fly

- He said “Who left?”

- (19)

- ka=

- 2sg.erg

- mẽ=

- du

- ho=

- ins

- s=

- 3sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- pjyankjâ

- trail

- Pânpaa

- Pânpaa

- hẽ

- erg

- “Let’s go see the trail”, Pânpaa [said].

An indirect quotation is the description of an illocutive act, rather than a demonstration of what was said. As seen in (20), indirect quotation shifts the perspective to that of the speaker.

- (20)

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- wa=

- caus

- too

- leave

- sõpâri

- witchcraft

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- Sykiã

- Sykjã

- hẽ

- erg

- “Hei is going to remove witchcraft”, said Sykjãi.

The fact that an indirect quotation is conveyed from the speaker’s perspective causes the main grammatical differences between direct and indirect quotations. The following two examples illustrate that. First, the person features change from what would have been a first or second person (21a, 22a) to a third person (21b, 22b). Second, there is also indexical shift in indirect quotations. Deictic elements that would display proximate features in direct quotation, such as mãja ‘this’ (21a) and jahã ‘here’ (22a), are instead realized by a non-proximate deictic element in (21b) and (22b).

- (21)

- a.

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- spk.irr

- kuri

- eat

- mãja

- this

- pakwa

- banana

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- “I will eat this banana”, he said.

- b.

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- ka=

- irr

- ti=

- nspk

- Ø=

- nadre

- kuri

- eat

- mãmã

- that

- pakwa

- banana

- He said that he will eat that banana.

- (22)

- a.

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- 1sg.irr

- wajãri

- eat

- issy

- this

- jahã

- banana

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- “I will make a fire here”, he said.

- b.

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- ka=

- irr

- ti=

- nspk

- Ø=

- nadre

- wajãri

- make

- issy

- fire

- ũwãhã

- there

- He said that he will make a fire there.

Indirect quotes also appear to be restricted to the deictic perspective established in the matrix clause, seen in the choice of realis for a future-oriented event (23), which would otherwise be realized with irrealis marking.

- (23)

- Toopytun

- old.man

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn,

- say

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- kwy

- go

- jy

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pjow.

- neg

- The old man said he won’t go.

There can be multiple levels of quotative embedding. In (24) the informant recounts a story from his childhood before contact, in which his grandfather Kâkjori gave him advice. We can see that there is a quotation introduced in the story by Kâkjori with sũn, inside of the first level of quotation, introduced with the narrative quote tijãri.

- (24)

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- nspk

- kân=

- 2sg.dat

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn,

- say

- ja

- this

- Ka=

- 2sg.erg

- ra=

- 3pl.abs

- nĩri

- have.sex

- pjow

- neg

- inkj-ara

- woman-pl

- inkjown

- neg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- tell

- “I will say this to you: Don’t have sex. No women”. he said.

It is worth stressing that quotation is not restricted to reporting speech events that took place in the past but can also extend to speech events that will take place in the future (25).

- (25)

- I bet that they will all say “Wow, that’s so strange!”

This is especially noteworthy for Panará. Panará socialization places a great importance on addressing explicitly what will be said at a given situation. In the following exchange, which I wrote down in my notebook after the conversation took place, a Panará elder was asking me about my impending trip back home and my future arrival at my parents’ house, and wanted to know what I would say to them. I started with (26a), and she continued with (26b), to which I replied (26c). As is usually the case, she looked satisfied with the small exchange.

- (26)

- a.

- jy=

- intr

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- pôô

- arrive

- puuahã

- far

- Brasil

- Brazil

- pêê

- abl

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- spk

- sũn

- say

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- hẽ

- erg

- “I have arrived from Brazil, far away” I will say.

- b.

- a

- q

- jy=

- intr

- a=

- 2sg.abs

- pôô

- arrive

- inkin?

- good

- ka

- 2sg

- nãpjâ

- mother

- hẽ

- erg

- “Did you arrive well?” your mother [will say].

- c.

- paa

- yes

- jy=

- intr

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- pôô

- arrive

- inkin

- good

- pytinsi

- very

- “Yes, I arrived very well.”

It is an open issue to what extent such exchanges are genuine enquiries or conventionalized, but they make future-oriented quotatives far from uncommon in the Panará language.

3.2 Panará quote constructions

The most unmarked and widely attested quote construction in Panará uses the verb sũn ‘say’. It is a transitive verb that takes one ergative and one absolutive argument. The absolutive, the internal argument, can be a DP such as a pronoun (27) or a noun phrase (28).

- (27)

- ja

- this

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- kân=

- 2sg.dat

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- I said this to you.

- (28)

- swankjara

- ancient

- jõ

- poss

- inpe

- true

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- hẽ

- erg

- I will tell something real of the ancients.

In its quotative role, sũn has a quotation as its internal argument. This can be a direct quotation, as seen in (29–30).

- (29)

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- prẽ

- who

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- too

- fly

- He said “who left?”

- (30)

- a

- q

- jy=

- intr

- py=

- dir

- a=

- 2sg.abs

- pôô

- come

- inkin

- good

- ka=

- irr

- ti=

- nspk

- kân=

- 2sg.dat

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- “Did you arrive well?” she will say to you.

The verb sũn can also introduce indirect quotations, which take the form of complement clauses, as in (31–32).

- (31)

- Kuupêri

- Kuupêri

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- inkin

- good

- pjow

- neg

- inkô-rãnkjo

- water-black

- Kuupêri said that he doesn’t like coffee.

- (32)

- inpy

- man

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- tõ=

- emph

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pyri

- take

- pjow

- neg

- atõ-sy

- gun-grain

- The man said to me that I didn’t bring any ammunition.

A second verb that introduces quotations is the verb jãri~inkjãri ‘to tell’ or ‘to call’, illustrated in (33) in its use as a conventional transitive verb.

- (33)

- pju

- measure

- jya

- long

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- mã=

- 3sg.dat

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- tell

- We called them “long [hair]”.

As a quote construction, the saying verb jãri can introduce both direct (34a, b) and indirect quotations (35), as seen in the following examples from a Panará myth where several bird species compete to see which one is fast enough to steal the black vulture’s fire.

- (34)

- a.

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sê=

- fast

- sũn

- say

- ankwa

- aim

- tomãsã

- curassow

- sê

- fast

- pjow

- neg

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- nkjãri

- tell

- They picked a curassow. “[It’s] not fast” they said.

- b.

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sê=

- fast

- sũn

- say

- ankwa

- aim

- prete

- trumpeter

- sê

- fast

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- sê

- fast

- pjow

- neg

- ti=

- 3pl.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- tell

- prete

- trumpeter

- hẽ

- erg

- They picked the trumpeter. “I am not fast”, said the trumpeter.

- (35)

- sâ

- eagle

- mẽ

- and

- kjẽnsâja

- sparrowhawk

- mẽ

- and

- sê

- fast

- pjoo,

- neg

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- inkjãri

- tell

- The eagle and the sparrowhawk were not fast, they said.

However, jãri is more marked than sũn. The form jãri is used almost exclusively as a saying verb instead of sũn in narratives, not only mythological but also heavily in oral texts belonging to recent history or personal events. The narrative dimension of jãri is discussed in the next section.

3.3 Narrative quotes and reportatives

The Panará verb jãri ‘say/tell’ is a quote marker that, just like sũn, introduces both direct and indirect quotations. But whereas sũn appears as an unmarked saying verb when introducing quotes, in its quotative use jãri is a more marked verb, heavily associated with reporting speech in the context of narratives. That includes the retelling of personal anecdotes and more generally narration of oral history and mythological texts. In these genres of speech, the quotative expression tijãri, as in (36), is very common.

- (36)

- a

- q

- ka=

- 2.erg

- rê=

- 2pl

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- npari

- hear

- rõ

- neg

- atõ

- gun

- tijãri

- 3sg.tell

- “Didn’t you hear the shots?” he said.

In fact, tijãri corresponds to a conventionalized or lexicalized use of the verb jãri~inkjãri (37) discussed in Section 3.2.

- (37)

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- tell

- He/she told.

Panará narrative quotes sit in a semantic area that also covers a reportative function (38). Also known as hearsay evidentiality, reportatives indicate that the information conveyed was aquired by the speaker from a source, rather than knowing the event directly or by inferrence. In the rest of the paper, tijãri will be glossed accordingly as a reportative in the examples.

- (38)

- pãpã

- all

- jy=

- intr

- tã=

- dir

- su=

- fin

- ra=

- 3pl.abs

- mõri

- go.plac

- tijãri

- rep

- panará

- Panará

- They all went to look for it, the Panará.

Reportatives should not be confused with strict quotatives. Even though the two categories are conceptually adjacent, reportative evidentials have scope over propositions, whereas quotative markers have scope over illocutions (Boye 2012: 32).

The reportative aspect of narrative quotes is further shown in (39), which reproduces a fragment from a telling of the Panará myth of how the guan stole the fire from the black vulture. As can be seen in the example sentences, no direct or indirect speech is introduced by tijãri. This suggests that it is reportative in function, although not a quote.

- (39)

- a.

- puuahã

- far

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- pêê=

- mal

- tã=

- dir

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- kjãren

- tell

- tijãri

- rep

- From far away he [the guan] spoke:

- b.

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- pêê=

- mal

- issê=

- fire

- jââ=

- fire.stick

- pyri

- take

- “I stole the fire!”

- c.

- puuahã

- far

- kõ

- per

- tã=

- dir

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pjâri

- follow

- tijãri

- rep

- nãnsôw

- black.vulture

- Far away the black vulture went after him.

- d.

- puuahã

- far

- jy=

- intr

- pêê

- ho=

- dir

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- too

- run

- tijãri

- rep

- Far away [the guan] ran with it.

The fact that the reportative use of tijãri is not identical to its quotative use can be seen in examples like (40), where it co-occurs with the properly verbal form of jãri. Here, jãri is a transitive verb that depicts the event of a group of animals giving instructions to the guan, and tijãri is used to indicate a reported source of information.

- (40)

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- mã=

- 3sg.dat

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- tell

- tijãri

- rep

- sõkrampjyâ

- guan

- mã

- dat

- And so they said it to the guan.

There is also a first-person idiomatic counterpart to tijãri: rêjãri (41). It is used to stress the commitment of the speaker towards the veracity of what they are saying (42).

- (41)

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- say

- I say it.

- (42)

- nãsisi

- sweet

- inpe

- true

- ikkjyti,

- tapir

- rêjãri

- rêjãri

- Man, tapir meat is very tasty!

4 Properties of Panará quotes

Since in Panará all subordinate clauses are internally headed, the syntactic shape of both direct and indirect quotations is identical to main clauses. Clausal position, case marking and argument cross-reference morphology are not particular to quotations, direct or indirect, as can be seen across the examples in (43–45).

- (43)

- Main clause

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- k=

- 2sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ka

- 2sg

- I know you [I saw you].

- (44)

- Direct quotation

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- k=

- 2sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- inkjẽ

- 1sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ka

- 2sg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- “I know you,” he said.

- (45)

- Indirect quotation

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- s=

- 3sg.abs

- anpun

- see

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- mãmã

- that

- ja

- this

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- He knew him, he said.

The very free constituent order of the Panará clause means that the position of the quotation relative to the quote construction is not fixed. Quotations can both precede or follow the quotative marker and can appear on either edge of the clause (46–47).

- (46)

- jy=

- intr

- tã=

- dir

- su=

- purp

- ra=

- 3pl.abs

- mõri

- go.plac

- tijãri

- rep

- panãra

- people

- The people went to get it [the fire].

- (47)

- rê=

- 3sg.erg

- mã=

- 3sg.dat

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sõri

- give

- sõkrepakoko

- guan

- mã

- dat

- jââ

- fire

- tijãri

- rep

- They gave the fire to the guan.

Prosodically, direct quotations are signaled by a raise in pitch, regardless of whether the person or character uttering the frame utterance would have been using a high- or low-pitched voice.

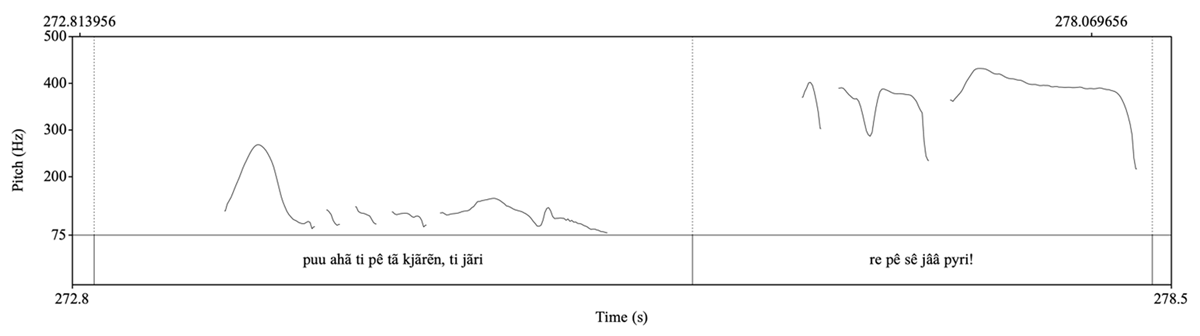

In (48) we can see the context for what is happening in the story from which example (49) is drawn. When compared to the framing narration in (49a), the direct quotation in (49b) is both realized with a falsetto voice and with a higher pitch, which can be seen in Figure 1.

- (48)

- While the black vulture was fishing, the other birds sent the guan to steal its fire. The guan then teases him.

- (49)

- a.

- puuahã

- far

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- pêê=

- mal

- tã=

- dir

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- kjãren

- tell

- tijãri

- rep

- From far away he [the guan] spoke:

- b.

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- pêê=

- mal

- issê=

- fire

- jââ=

- fire.stick

- pyri

- take

- “I stole your fire!”

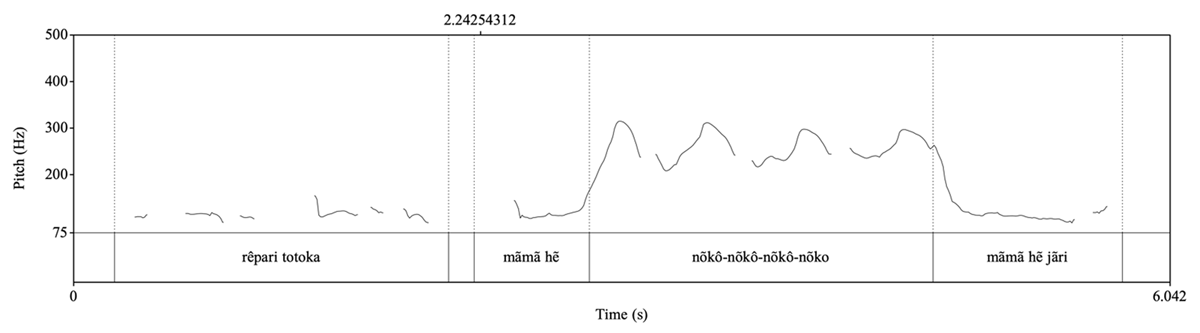

Similarly, the onomatopoeic call of the marmoset in (50) is said with a higher pitch than the rest of the sentence, and in a falsetto voice, as shown in Figure 2.

- (50)

- rê=

- 1sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pari

- kill.plac

- totoka

- marmoset

- mãmã

- this

- hẽ

- erg

- nõkô-nõkô-nõkô-nõko

- <animal call>

- mãmã

- this

- hẽ

- erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- jãri

- tell

- I hunted marmosets. It goes “nõko-nõko-nõko-nõko,” this one says that.

There is also a comma pause indicating the quote boundary (marked with # in the following two examples). Unlike high pitch, which is exclusive to direct quotations, the prosodic break can be present in both direct and indirect quotations.

- (51)

- ka=

- irr

- Ø=

- spk

- kuri

- eat

- mãja

- this

- pakwa

- banana

- #

- mãra

- 3sg

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- “I will eat this banana”, he said.

- (52)

- sâ

- eagle

- mẽ

- and

- kjẽnsâja

- sparrowhawk

- mẽ

- and

- sê

- fast

- pjoo

- neg

- #

- rê=

- 3pl.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- inkjãri

- tell

- The eagle and the sparrowhawk were not fast, they said.

As for the constituency of quotes, a single quote, direct or indirect, can host more than one clause (53–54).

- (53)

- toopytun

- old-man

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- sũn

- say

- jy=

- intr dir

- py=

- dir

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- kwy

- go

- jy=

- intr

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- nto-

- eye-

- kâ-

- skin-

- ti

- heavy

- The old man said he’s leaving, he’s sleepy.

- (54)

- ju

- q

- rin

- loc

- issy

- fire

- prẽ

- who

- hẽ

- erg

- ti=

- 3sg.erg

- ra=

- 1sg.abs

- pêê=

- mal

- Ø=

- 3sg.abs

- pyri

- take

- tijãri

- take

- “Where is the fire? Who took it from me?” he said.

5 Conclusion

The Panará people make extensive use of quotation in their daily lives, and their language provides them with several grammatical strategies for doing so. These are summarized in Table 2.

Properties of direct and and indirect quotation in Panará.

| Direct | Indirect | |

|---|---|---|

| Full clause | yes | yes |

| Smaller than clause | yes | yes |

| Bigger than clause | yes | yes |

| Indexical shift | no | yes |

| Acute pitch | yes | no |

| Comma break | yes | yes |

| Questioned | yes | yes |

| Negated | yes | yes |

As we have seen, quotes are similar to phrases or full clauses in Panará in terms of their morphosyntax. In particular, they present no properties that would not be expected from complement clauses: a full verbal complex, ergative-absolutive case marking, and pre- and postverbal clausal positions. Panará has several quotatives to introduce quotations without the need of a dedicated framer, all of which are verbs—and the verb itself can sometimes undergo elision. The narrative quote has a degree of lexicalization and coexists with a closely related reportative. If a hearer is introduced, it does so as a dative participant.

Direct and indirect quotations are not entirely identical. However, as it stands, there is no clear syntactic or morphological diagnostic to tell them apart. One of the key differences is indexical shift, observed only in indirect quotations. The second diagnostic is prosodic, namely the presence of a high pitch assigned to a direct quotation.

The information brought up in this paper points towards avenues of future research on the topic of quotation in Panará and, more generally, the distinction between different types of embedded clauses. One phenomenon that did not become clear during research on this topic was the matter of extraction from quotations. It is quite clear that indirect quotes allow for extraction of an argument to the matrix clause, but the picture is not clear for direct quotes. The status of tijãri as a narrative-dedicated quotation marker and as a reportative is also an issue that needs further research, as it is one of the few grammatical elements in Panará with evidential semantics. The potential use of both tijãri and rêjãri as discourse elements that target elements of the speech act, and to what extent they contribute discourse-related information, is also a matter for further research. As an exceptional Jê language, this study of quotation in Panará also raises a diachronic question regarding the status of Panará within the Jê family. Future research will be necessary to provide information about the degree of retention and innovation of Panará concerning the grammatical properties of Jê quotation strategies.

Notes

- Note, however, that a more recent classification proposal places Panará outside of the Northern Jê languages (Nikulin 2020). [^]

- Unmarked examples are from Panará and were collected by the author during fieldwork in the village of Nãnsêpotiti. The abbreviations used in glossed examples are the following: abl ablative, abs absolutive, acc accusative, adre addressee, asp aspect, caus causative, com comitative, dat dative, dir directional, erg ergative, fact factive, fin finite, ines inessive, intr intransitive, irr irrealis, iter iterative, lg long verbal form, loc locative, mal malefactive, nadre non-addressee, neg negation, nfut non-future, nom nominative, nspk non-speaker, per perlative, pl plural, plac pluractional, purp purposive, q question, rep reportative, sg singular, sh short verbal form, spk speaker, tr transitive. [^]

- The jy morpheme in (10) is a modal clitic that indicates realis in intransitive verbs; its transitive equivalent is null. Even though it is glossed as intr, it also serves as an exponent of realis mood. [^]

Acknowledgements

I want to express my heartfelt gratitude to the Panará people, especially the people in the village of Nãnsêpotiti. My deepest thanks to the informants who contributed to one more step in my understanding of the Panará language, and to the research presented here: Perankô, Sokren, Kânko, Kypakjã, Akââ, Jôôtu, and Krenpy. I am also extremely grateful to COSY-ZAS for funding fieldwork in 2019 that initiated this research, and to Suzi Lima and Tonjes Veenstra, the editors of this volume and the organizers of a delightfully interesting workshop in the Amazonian city of Belém, as well as the participants for their feedback and discussion. I also thank two anonymous reviewers for their feedback on an earlier version of this article and Lise Dobrin, editor at Language Documentation and Description.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Bardagil, Bernat. 2018. Case and agreement in Panará. Groningen: University of Groningen dissertation.

2 Bardagil, Bernat. 2019. Person, case, and cliticization: The Panará PCC. In D. K. E. Reisinger & Roger Yu-Hsiang Lo (eds.), Proceedings of the Workshop on Structure and Constituency in the Languages of the Americas 23. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

3 Bardagil, Bernat. 2020. Number morphology in Panará. Linguistic Variation 20(2): 312–323. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1075/lv.00023.bar

4 Bardagil, Bernat & Kim Groothuis. 2023. Finiteness across languages: A case study of the Jê family. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Structure and Constituency in the Languages of the Americas 25. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

5 Boye, Kasper. 2012. Epistemic meaning: A crosslinguistic and functional-cognitive study. Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783110219036

6 Clark, Herbert H. & Richard J. Gerrig. 1990. Quotations as demonstrations. Language 66(4): 764–805. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/414729

7 Davis, Irvine. 1966. Comparative Jê phonology. Estudos Lingüísticos: Revista Brasileira de Lingüística Teórica e Aplicada 1(2): 10–24.

8 Dourado, Luciana. 2001. Aspectos morfossintáticos da língua panará (jê) [Morphosyntactic aspects of the Panará language]. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas PhD dissertation.

9 Giraldin, Odair. 1997. Cayapó e Panará: Luta e sobrevivência de um povo Jê no Brasil central [Cayapó and Panará: Fight and survival of a Jê nation in central Brazil]. Campinas: Editora Unicamp.

10 Heelas, Richard. 1979. The social organization of the Panara: A Gê tribe of central Brazil. Oxford: Oxford University PhD dissertation.

11 Nikulin, André. 2020. Proto-Macro-Jê: Um estudo reconstrutivo [Proto-Macro-Jê: A reconstructive study]. Brasília: University of Brasília PhD dissertation.

12 Nonato, Rafael. 2014. Clause-chaining, switch-reference, and coordination. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology PhD dissertation.

13 Rodrigues, Aryon. 1999. Macro-Jê. In Robert M. W. Dixon & Alexandra Aikhenvald (eds.), The Amazonian languages, 165–206. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

14 Rodrigues, Aryon & Luciana Dourado. 1993. Panará: Identificação lingüística dos Krena-Akarore com os Cayapó do Sul [Panará: Linguistic identification of the Krena-Akarore (sic) with the Southern Cayapó]. Reunião Anual da Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência 2: 505.

15 Salanova, Andrés. 2007. Nominalizations and aspect. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology PhD dissertation.